Black Texans Reflect on Racial Justice after a Singularly Difficult Year

The killing of George Floyd in May 2020 inspired Texans of all colors to take to the streets to speak up against systemic racism. Protests occurred around the state, and the words “Black Austin Matters” appeared in giant yellow letters in several Texas cities, including along Austin’s Congress Avenue leading to the state Capitol.

At the same time, a pandemic that has disproportionately affected black Americans continued to ravage the country — COVID-19 has killed almost 40,000 Texans to date.

Eight months later, during the inauguration of President Joe Biden, Amanda Gorman, a 22-year-old African-American poet, acknowledged the country’s difficulties and exhorted all Americans to work for a more just union.

“So let us leave behind a country better than the one we were left with,” Gorman said. “We will rebuild, reconcile and recover and every known nook of our nation and every corner called our country, our people diverse and beautiful will emerge, battered and beautiful”

During February and March, Reporting Texas correspondents will share interviews with Black Texans from different parts of the state, different professions and different perspectives. Subjects will discuss the state of the fight for racial justice and how they think Texans can best move forward after a trying year. Check back for updates.

— Mizelle Mayo, Madi Donham and Jillian Price

James Williams, Austin

Published Feb. 24

James Williams stands outside Austin Shoe Hospital on Saturday, Feb. 6, 2021, in Austin, Texas. Lindsey Staskus/Reporting Texas

When James Williams was 16, he visited his older sister in Austin. Williams, who was living with his parents in Lake Charles, Louisiana, was blown away by Austin’s laid-back vibe. Two years later, in 1988, he moved to the city. A few months after moving, Williams landed a job as a cobbler at Austin Shoe Hospital. He’s worked there since.

Reflecting on the last year, Williams said the racially-charged presidency of Donald Trump and tragedies like the killing of George Floyd and other black people at the hands of police have presented an opportunity for people to band together to fight for justice.

“A lot of people would wash over it and say there is no racism in America, but Donald Trump let a lot of people see that we’re not as far as we thought we were,” he said.

Williams sees the push for racial justice is a part of a centuries-long struggle. “We’re the only people with ancestors that were brought here as slaves,” Williams said. “They had to fight for their freedom, and then the fight for equality in a society that thinks of them as less than since the day [they] were brought here.”

Williams, who moved to Pflugerville in 2004 from Austin, said he is concerned by structural factors such as gentrification and escalating taxes that are pushing black people out of Austin. Improving educational and employment opportunities could lure back families back to Austin, he said.

A criminal justice system that disproportionally punished black people also needs to be addressed, Williams said. A more flexible approach to court dates would help some Black people prosecuted for minor charges hold on to steady jobs, Williams said. They could move a court date because of work or childcare, he said.

Williams, who wears shirts such as “Don’t get mad. Get Even Vote!” and “The fight is not mine, It’s ours,”said it’s important to continue to engage people in conversations about the state of race relations in the community.

“We have to inspire people that come after us,” he said.

—Sumaiya Malik

Sarah Miller, Austin

Published Feb. 24

Photo courtesy of Sarah Miller

Sarah Miller says she has moved four times since she arrived in Austin in 2013. Each time Miller moved, she made a piece of home decor to celebrate her new digs.

In 2018, Miller turned her hobby into a home decor business called Awkward Auntie.

The business name came to Miller, 34, while reflecting on what family means to her. As a literal and honorary aunt for family and friends, she aims to be a source of strength to those around her.

Miller couldn’t stop thinking about family after the killings of George Floyd and Breona Taylor. She worried people would view her 19-year-old nephew — who graduated from high school in South Carolina in May — as threatening.

“It doesn’t matter what this kid does, he’s the smartest kid I know, and still, somebody else can decide who he is. Somebody else could define him,” Miller said.

As a Black-owned business, Awkward Auntie received an outpouring of support from customers in 2020. Although grateful, Miller struggled with guilt and thoughts of not being worthy of the attention she received.

“It almost felt like it was just happening in response to tragedy and not because of my work,” Miller said. “But I want to offer encouragement for Black people who have the same thoughts: You’re meant to be successful right now, and your success will breed success for others.”

Miller enjoys posting stories of influential Black women on Awkward Auntie’s social media for Black History Month. At the same time, white people’s assumption that Black people should always be available and open to discussing racism can feel oppressive.

She never imagined moving to Texas, a place she considered strange and daunting until graduating from the University of New Hampshire in 2009. But in 2013 Miller took a chance on what she called the best blind date ever after joining her university friends in moving across the U.S. to Austin. The 34-year-old splits time between Austin and her family home in Londonderry, New Hampshire.

— Madi Donham

Terren Moore, Greenville

Published Feb. 24

Photo courtesy of Terren Moore

Terren Moore, 24, works as an insurance agent providing auto, home and life insurance in Greenville, about 51 miles northeast of Dallas. On the weekends, Moore spends time farming on 30 acres just outside of the city limits. Greenville, population 27,000 is 55% white, 24% Hispanic and 15 % African American.

The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 reinforced Moore’s belief in the importance of being as non-threatening as possible when dealing with police. Police stopped him in February for driving too fast, he said. “I am respectful and calm. I know there are racist cops out there.”

Moore, who has an agricultural science degree from Tarleton State University in Stephenville, grows turnip greens and collard greens in winter and purple hull peas, green peas and okra in spring. He said he is the only black farmer in the Greenville area.

Other farmers are generally kind when they interact with him, but he has faced some racism, Moore said. “I’ve been called a beggar before … People have made fun of my hair,” Moore said. “I was like, man that hurts!” he said.

“I know there are lots of bad things going on, but there are more good things going on and there is bad,” Moore said regarding race relations in Texas.

During his farm work, Moore interacts mostly with white people. He employs several teenage helpers seasonally. “Most of my farm boys are white,” he said.

Donald Trump’s heated rhetoric on racial issues hasn’t much of an impact on how people feel about the state of race relations in the country, Moore said. “If one person can change your opinion about how you look at things, that person is weak,” Moore added.

— Sumaiya Malik

Meesha Westmoreland, Amarillo

Published Feb. 24.

Courtesy of Meesha Westmoreland

Meesha Westmoreland didn’t go into 2020 thinking she would be the leader of the Black Lives Matter protests in Amarillo. As a freshman at Tascosa High School, she felt optimistic about 2020 and had begun to fall in love with debate.

When the pandemic hit in March, that optimism began to fade. She felt isolated from the rest of the world.

“I feel like I missed out on something,” Westmoreland, 15, said of her school switching to virtual learning in March. She is now homeschooled and no longer attends Tascosa High School.

Westmoreland admits that without the isolation of the pandemic, she might not have had enough time to process what came next.

In early May, the video of Ahmaud Arbery’s killing went viral. Arbery, a 25-year old, unarmed Black man, was killed while on a jog in his Georgia neighborhood by three white men who wrongly suspected him of looting a house under construction. Three weeks later, a Minneapolis police officer dug his knee into George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds.

Cooped up in her room, Westmoreland’s followed the news of Arbery and Floyd closely.

“At that point my gears were just turning, so we tried to plan a protest,” Westmoreland said.

It all started with a text message, as Westmoreland asked one friend if he would join her if she led a protest. “Absolutely,” he responded.

Westmoreland had a moment of doubt.

“We’re 15 years old. How are we going to do this?” she asked herself.

But as she started reaching out to friends and organizing via a Snapchat group, she realized that many other young people in the Amarillo community supported her cause. The Snapchat group swelled to 30 people.

Throughout the summer, Westmoreland led protests with a simple, yet powerful, message.

“One of our main things was peace, love and unity in our community. That was what we were trying to get out there,” she said.

However, her group faced backlash from an Amarillo for Trump group. In June, the Trump supporters showed up in trucks to the second Black Lives Matter rally at John Stiff Park. Many carried guns and waved Trump and American flags.

In the fall, she decided to stop holding rallies, in part because of the backlash and intense political climate surrounding the election.

“We’ve been a little bit on the quieter side, which I hate, and I wish we didn’t have to do, but we have to for safety reasons,” Westmoreland said.

Despite pausing protests in Amarillo, Westmoreland clings to the optimism she felt as her classmates came together to support Black Lives Matter last year.

“I don’t want to be stupid about my hope,” she said. “But I know that if I lose it, I might miss out on something so beautiful.

—Benton Graham

Jonah Elijah, Houston native

Published Feb. 28.

Courtesy of Jonah Elijah

Jonah Elijah, 26, grew up in Houston with George Floyd’s nephew. That’s why, when Elijah painted a Black Lives Matter mural in February 2021 outside Floyd’s former high school in Houston’s Third Ward, it felt extra personal.

“It just clicked to me how close to home this was,” Elijah said. “I always feel something close to home when we are out here being killed by police officers … but this one really just hit close,” he added.

Elijah is a painter, sculptor and performance artist. He was born and raised in Houston and has been living and working in Los Angeles since 2018. His art has been commissioned by Houston’s Station Museum of Contemporary Art and appeared in installations around the city.

Elijah’s mural was unveiled on Feb. 8 on the street in front of Jack Yates High School, where Elijah is also an alum. It was commissioned by Harris County Commissioner Rodney Harris, Houston Society for Change and 88 C.H.U.M.P., a non-profit organization that aims to get minority voters to the polls and was created by Floyd’s high school football teammates.

“It was fun growing up in Houston,” Elijah said. “We always had things to do outside, playing with friends, playing basketball.”

When asked what people in the community can be doing to help improve race relations, Elijah said, “I think just being able to understand each other’s plight, and not turning a blind ear to one’s plight and understanding the history of race relations.”

“I think right now we need to get into the mindset of fighting for ourselves and fighting for our youth,” Elijah added, “so that they can have a better future and not go through what we have to go through.”

—Harrison Young

Marty Jones, Austin

Published Feb. 28.

Courtesy of Marty Jones

With a long career in the film industry — owning production companies and managing studios — Marty Jones, 57, has often been the only Black man in the room, he said.

“When I started my career, it was extra unusual for a young Black man to be pursuing a career in Hollywood,” Jones said. When he started a family — Jones has three children aged 19, 22 and 25 — he decided to make sure his creative endeavors would “make life better for them and represent our heritage and our history.” Jones has produced several films with Black stars and directors. Jones also leads Black Film Geniuses, a film collective that promotes Black women filmmakers.

Jones’s family is the key to his achievements, Jones said. Knowing they support him gives him the confidence and grounding that have led to his success, he added.

Jones moved to Texas in 2019 after spending time working in the movie business in Oregon, Virginia and California. After his move, Jones became director of Austin Studios and has pulled off the unenviable task of keeping film and television projects going at the studio during the COVID-19 pandemic.

He hopes white people see things more clearly in the wake of the George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests and continue to get involved in the fight for “more equitable, permanent change.”

“I’m asking for 30 million white people in America to stay as committed to where they were in the spring of last year,” Jones said.

“I want all that righteous indignation to be maintained…and that they would walk not only shoulder to shoulder with us, but in some cases ahead of us to stay committed to long-term change in this country,” Jones said.

— Harrison Young

Alta Alexander, Austin

Published March 3.

Courtesy of Alta Alexander

Everything changed for Alta Alexander when she woke up to a 3:30 a.m. phone call from the police on June 1. Police officers were calling to inform Alexander, 56, of a fire in the barber shop next to her East Austin clothing store. Smoke front the fire destroyed every item of Altatudes merchandise.

The damage coincided with the fourth consecutive day of protests against police brutality in Austin.

She doesn’t believe that the downtown protests and East Austin fire were connected, but the source of the fire remains a mystery, Alexander said. Despite not having answers and closure, she’s trying to move forward.

“The spotlight has been shone on injustices within the African American community, but there is still a tremendous racial divide,” Alexander said after reflecting on how the fight for racial justice has changed since that summer.

One lesson learned: People should also support Black-owned businesses even when there isn’t a tragedy, Alexander said.

Alexander moved to Austin from rural East Texas with her family when she was 12 years old.

A love of fashion has always been a part of her life. She grew up making mini department stores out of recycled shoeboxes. Her grandmother and cousin were impressive seamstresses, and Alexander remembers circling her favorite outfits in Sears clothing catalogs as they sewed.

Alexander’s husband gifted her the retail space for Altatudes four years ago on Valentine’s Day, and the store opened seven months later, on Sept. 18, 2017. She was attracted to the culture and history of East Austin. To her knowledge, Alexander is the first and only African American woman to own an upscale womenswear boutique in the broader Austin community, she said.

Alexander grounds herself in the words spoken by Kamala Harris during her first speech as vice president — she may be the first, but she won’t be the last.

“So if there are other Black females who are looking to do the same thing — more power to them,” Alexander said.

Altatudes remains online-only as Alexander waits for the reconstruction of the interior of her store.

— Madi Donham

Marvina Case, Austin

Published March 18.

Texans United for America was formed in 2017 when Marvina Case, 45, and three other mothers “who didn’t like the way the world was going” decided to do something about it, Case said.

The organization, which doesn’t claim a partisan affiliation, has organized several rallies in support of Donald Trump. Members strongly support Trump’s economic and foreign policies and share his disdain of political correctness, Case said.

“Either you have a free mind or you’re a slave,” Case said in reference to her support of Trump.

Case takes issue with the Democrats’ platform, which she labels open borders, affirmative action and access to abortion. The platform hurts Black Americans, Case said. She also criticizes Vice President Kamal Harris’ record as California Attorney General — specifically Harris’ involvement in several cases that led to wrongful convictions. Case also is quick to criticize the Black Lives Matter movement, which she said is disproportionately white.

Black Republicans face scrutiny for their beliefs, Case said, but Case said she could care less — she is fine with being labeled a “crazy, bible-thumping person.”

“I don’t think it’s important that we hear black voices, I think it’s important that we hear different voices,” she said. “I don’t want to see the word Black put in front of anything, or white or Hispanic because it doesn’t matter.”

Case hails from Gary, Indiana, sometimes called the murder capital of the world in the 1990s — a harsh environment that shaped her politics. She was active in the Republican party since she could vote. Since graduating from Purdue University, Case has done orphanage outreach in South America and Bangladesh, estimating that 1,500 children around the world call her “mom,” she said.

Her background in technology — Case works in sales for the technology company TaskSuite — has given her insight into Donald Trump’s claims that the 2020 election was stolen — she said.

“Looking at the numbers and knowing the machines and being a data scientist, I can tell you that he did win. I am 100 percent sure he won the election,” she said. “The numbers don’t add up — it’s just simple mathematics.” (Trump’s election fraud claims are unsubstantiated and have been debunked by multiple news outlets.)

“People need to get over their stereotypes — I don’t like fried chicken and watermelon,” she said. “I don’t believe in the American dream, I believe in the American reality.”

— Ramón Rodriguez

Otis Arnold, Austin

Published March 19.

Otis Arnold sits in his backyard in East Austin, on March 18, 2021. Arnold and his siblings, specifically his sister Carolyn Thompson-Powell, are weekend ranchers who raise cows on a farm outside of Austin. Evan L’Roy/Reporting Texas

Otis Arnold is a weekend farmer who raises cows on a 200-acre family property in Cedar Creek, 11 miles west of Bastrop. During the week, he lives in East Austin and works as a mechanic and transports cars between dealerships.

Arnold, 61, is one of 16 siblings. He and his family have 100 cows and two bulls, which they use for breeding, he said. A young cow weighing about 500 pounds will fetch about $600 or $700, he said.

There are no modern trackers on the cows. “Nobody will come to take them because there are locks on the gates,” he said.

Arnold, who was born and raised in Austin, encounters prejudice everywhere he travels, mostly Bastrop, Round Rock and Tyler, he said.

He owns a house on Delano Street, next to Springdale Park in East Austin. He bought the home from his Aunt, who built the house in 1959. Developers who are buying property in the area have contacted him about selling the house.

“They don’t want to give me what it’s worth,” he said, “I tell them if they want my house give me $500,000 because where can I go buy a house for $200,000?”

In general Arnold does not enjoy talking about racial prejudice in Austin, but he did say the assumption that black people are poor bothers him. There are wealthy African Americans in Austin who simply don’t flaunt their wealth, he said.

“They dress normal,” he said. “They [will not buy] cars and stuff like that. They are people who’ve got money.”

—Sumaiya Malik

Jastin Taylor, Midland

Published March 26.

Courtesy of Jastin Taylor

By day Jastin Taylor is a 38-year-old hospital-based advisor for the Texas State Department of Health and Human Services. At night he transforms into “The Living Proof,” a wrestler who delivers both motivational messages to his fans and his “Burden of Proof” move to his opponents. In his signature move, Taylor suspends his opponent in the air, flips them and finally slams them on their back.

“As far back as I can remember, I’ve always been a fan of professional wrestling. It was something that I grew up on. Growing up, I was the nerdy kid that liked wrestling,” Taylor said.

Courtesy of Jastin Taylor

Taylor’s motivational messages are often practical — practicing time management and goal setting, for example — but he also tackles big, philosophical questions. “What motivates you?” Taylor asked in a recent Facebook post. “Sometimes the answer to that question is the difference between a good life and a bad one.”

To make his two careers work, Taylor meticulously cultivates his wrestling body by skipping lunch to exercise. He also does high intensity workouts, yoga and stretching everyday to maintain peak form for his wrestling matches that take place across the country on weekends.

While Taylor loves his second job, he says that being a person of color in wrestling has its challenges. The wrestling community often tries to typecast him in stereotypical Black characters, such as preachers, dancers and hip hop artists, he said.

“I do feel like I have to work harder. I do feel like I have to carry myself a certain way to avoid falling into some of the Black stereotypes,” Taylor added.

During the racial justice protests during the summer of 2020, Taylor saw an opportunity to use his voice. However, he also worried that speaking out about Black Lives Matter could alienate his fanbase and limit his ability to book shows.

“Being a part of those hard conversations about race definitely had its struggles. I lost plenty of friends, whether it be on social media or in real life. But I’ve also made some friends,” Taylor said.

Despite these challenges, Taylor can’t help but revert to his Living Proof persona when talking about the future of racial justice.

“Black people out there and minorities out there that are just having a tough time, all I want to say is just don’t give up. Your strength is the best thing that we have,” Taylor said.

– Benton Graham

Zach and Delisa Harper, Austin

Published March 30.

Delisa Johnson and Zach Harper, the co-founders of Funky Mello, pose for a portrait at Mueller Lake Park in Austin, Texas, on March 10, 2021. Johnson and Harper started Funky Mello about three years ago originally making rice crispy treats. The duo eventually transitioned to making vegan marshmallow treats when they saw there was a gap in the market. Hannah Burbank/Reporting Texas

A small dessert shop in New York City was the inspiration for Houston natives Zach and Delisa Harper. After watching the shop create marshmallows from scratch, the Harpers began to think they could do it.

In January 2018, Funky Mello began producing the country’s first vegan, gluten- and carrageenan-free marshmallows, the Harpers say.

Along with creating inclusive treats, the couple hopes to be inclusive in propelling like-minded Black business men and women in the community.

“We only hope that we are able to act as a role model and inspiration to encourage them to act on their dreams and hopes and connect with each other, especially in these times,” Delisa Harper said.

The couple is working to make connections with influential Black business owners, including Joi Chevalier from The Cook’s Nook, an East Austin business that is encouraging Black entrepreneurship through her commercial kitchen as well as maintaining business connection with several Houston businesses.

The advice they have for non-Black business owners is simple — reach out and open yourself up to the people around you, no matter their race.

“There are a lot of allies. I would not be where I was quite frankly if I didn’t just open myself to other people … not just people who are African-American but people who are Caucasian, Asian, etc. I had huge allies in those spaces too,” Zach Harper said.

“Continue to reach out to the community and tell people what you can bring to the table,” he said. “You will find out very quickly in my opinion other people that really want to help you.”

— Madelyn Gee

Isaiah Wilson, Dallas

Published March 30.

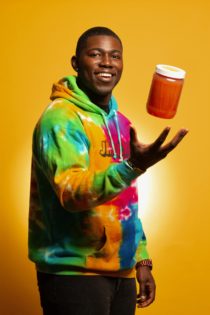

Courtesy of Isaiah Wilson (The Pickle Plug)

Isaiah Wilson, 23, also known as The Pickle Plug, has been running his Dallas-based flavored pickle business since 2016. While a finance major at the University of North Texas, Wilson and his roommate needed a way to make extra money. What started out as a hobby has turned into a business that now ships across the country.

To get the flavors right, Wilson looked up recipes online and reached out to his family. He ultimately came up with his own recipe through “trial and error,” he said. Wilson started out selling on campus, and as word spread, demand increased.

With the help of his mom and two younger sisters, Wilson opened a physical retail location last fall. He sells close to a dozen, such as strawberry-kiwi and best-sellers, blue-raspberry lemonade and mixed berry.

Because of the events of the past year, as a Black man and the owner of a Black business, Wilson finds it important to support other up and coming Black businesses.

“Supporting Black businesses is a top priority for me,” he said.

To support other Black businesses, Wilson orders different products, then promotes and reviews them on his YouTube channel, Zay’s Reviews. The reviews encourage viewers to also learn about and support Black businesses that they may not have known about before.

Like many other Black Americans, Wison has been getting questions about what the next step in the struggle for racial progress.

“What do I do?” he said, is the question he hears from his counterparts.

“For me, the charge has always been trying to point them to the right resources,” Wilson added.

This includes books and articles written by voices in the Black community who promote the discussion of racial issues. These voices could include Emmanuel Acho, author of “Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man,” and Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of “Between the World and Me.”

— Jillian Price

Emmanuel Gyang, Dallas

Published March 30.

Courtesy of Emmanuel Gyang

Emmanuel Gyang, 24, along with close family members, founded Mama Africa’s Apparel in Nashville 2016. When Gyang moved to Dallas in 2018 after graduating from Tennessee State University, the business moved also.

Originally from Accra, Ghana, Gyang and his family wanted a way to bring authentic African clothing to the U.S, while also giving it a splash of Western influence, he said.

While participating in an internship in Ohio with a law publishing company in 2016, Gyang visited a Jazz Festival where an Asian man was selling over-charged, non-authentic African clothing, leading Gyang to want to sell his own apparel.

“It was kind of a slap in the face, you know, being a person of the African diaspora,” Gyang said.

Mama Africa’s Apparel, turned into a business that helped support Gyang and his family, who are also entrepreneurs. His parents own a car business in Nashville.

Gyang says it’s important to support Black businesses.

“It would be great to see more financial support [for Black businesses] being added, because we see the social support,” Gyang said.

Gyang believes that a way to increase that financial support is through voting and placing progressive leaders in positions where they can promote initiatives that support Black-owned businesses. Older business owners should also help mentor younger entrepreneurs, he added.

As Americans continue to work toward racial equity, all Black Americans need to remember the ties that bind them, Gyang said.

“We are one,” he said.

— Jillian Price

Amanda Reid, Austin

Published April 1.

After taking calligraphy classes so she could write her wedding invitations, Amanda Reid, 32, fell in love with the ancient art. Reid, who works as a physical therapist by day, started the calligraphy and engraving business Amanda Reid Designs in 2019.

Shortly after starting her company, Reid noticed that most of the calligraphy professionals she came across were white, so she started a Facebook group called Calligraphers of Color.

“That is how I am dealing with the lack of diversity in the calligraphy space. I started my own little community and it has grown,” Reid said. The group has 14,300 followers and counting.

While Reid has been able to find community through Calligraphers of Color, facing daily interactions with white people can be challenging, she said.

“The main challenge has been the lack of representation and diversity. When there is a lack of representation, it can come off as, ‘Maybe this industry is not for people like me,’ which are comments I have heard from other BIPOC [Black, indigenous and people of color] calligraphers who have found the same challenge,” Reid said.

“I shared a video last year discussing the importance of representation and how in the calligraphy space ‘White hands are the default.’ It is hard to find instructors and leaders in the calligraphy and lettering community that look like me and I’m hoping to change that,” Reid said.

Reid has one main piece of advice to those who don’t identify as people of color — be open and be kind.

“It’s really easy to dismiss experiences that are not your own. It’s hard to relate to something that you’ve never had to deal with or go through,” Reid said.

“Just being open to other people’s hearts and being willing to listen and put your own biases aside would make a lot more progress than being resistant or thinking someone else’s experience are not that big of a deal,” Reid said.

— Madelyn Gee

Chi Ndika, Austin

Published April 1.

Chi Ndika, 25, sells her avocado based ice cream at the Mueller’s Farmers Market on Sundays. She started the vegan Luv Fats Ice Cream because her mom had a sudden dairy allergy. Mizelle Mayo/Reporting Texas

When Chi Ndika’s mother developed a dairy allergy in 2018, Ndika, decided to create a vegan ice cream for her. Three years later,Luv Fats Ice Cream is thriving in various locations such as the Mueller’s farmers market on Sundays, Bee Grocery and Mozart’s Coffee.

The company’s ice cream main ingredients are avocado, coconut milk and raw cane sugar. Ndika’s ice cream flavors include butter pecan, coffee, vanilla, olive oil and biscoff caramel.

Ndika, 25 gives credit to the Austin community and her family for keeping her mind, spirit and business afloat during the last year.

“I was lucky enough to start my business at a market that featured Black businesses. It was called the Melanated Marketplace, and it was at Kenny Dorham’s Backyard,” on East 11th Street, Ndika said. “That was one of the first places that I was able to sell my product to a lot of Black people and people in general.”

“I was able to learn from other Black mentors that have been in the city and creating for longer than I have, Ndika added. “It was nice to make those connections,”

Building Luv Fats Ice Cream has helped Ndika feel empowered as a Black woman.

Ndika is a native Austinite. “I think that a lot of people like to come here and say that [Ausitn is diverse],” Nidka said. As someone that grew up here, there’s just a lot less Black people that I see.”

Ndika says her mother is her inspiration to work hard. “It’s really encouraging to see a Black woman to work hard every single day for what she wants,” said.

—Mizelle Mayo

Pastor Kenneth Kemp, San Antonio

Published April 19.

Pastor Kenneth Kemp moved to Texas after completing college at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in 1988. In addition to practicing medicine as a family physician, Kemp is an ordained Baptist minister at the Antioch Missionary Baptist Church in San Antonio.

“It’s always been a challenge with balance. However, every physician, every human being, regardless of what your profession is, has to engage in work life balance,” Kemp said.

As a physician and a pastor, listening is the most important skill for both physicians and pastors, Kemp said. Kemp’s faith helped him cope with the pandemic and racial upheaval of 2020.

“What you do is to speak to the real issues of people, and you don’t try to make everything a pie in the sky solution. It’s been difficult but manageable. What is difficult is that people have been dying around you in your congregation. That’s difficult.” Kemp said.

Kemp said hehas experienced discrimination by police various times in various states while completing new assignments as a physician. In 1995, Kemp and his wife were on their way to North Carolina for a new assignment when the police pulled him over and searched his van. They suspected he was a drug dealer, Kemp said.

“I felt helpless to resist in the middle of nowhere with gun-toting cops at my vehicle door. I gave no indication that I was involved in anything nefarious, though I suspect being a young Black man and wearing a warm-up suit may have fit their profile for criminal activity,” Kemp said in an email.

Tne killing of George Floyd in April 2020 was just one incident, but it was representative of the unequal treatment of Black people have faced for centuries in the United States.

From Trayvon Martin, to Michael Brown, to Philando Castille, to Eric Garner, to Botham Jean, to Sandra Bland, to Breonna Taylor, to massive throngs of African Americans not accounted for in news stories; it was just too much. Enough is enough,” Kemp. said.

-Mizelle Mayo

Sydney Jones, Beaumont

Published April 19.

When Sydney Jones served in the Air Force, the country was being torn apart by the 1960s civil rights movement. Most Air Force barracks were segregated, mess halls were segregated, and, when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, the Air Force didn’t allow Jones to protest.

Jones, 91, was an Air Force sergeant stationed in California for most of his career. As a sergeant he was allowed to sleep in the white barracks, but he refused, choosing instead to sleep with Black airmen

“I’m gonna sleep with my men,” he said. “I’ll work for you, but I don’t have to live with you. I didn’t socialize with them.”

Jones lives in Beaumont, where he grew up. When he was a teenager, in 1943, chaos engulfed Beaumont after a white woman accused a black man of rape.

A mob of 4,000 marched to the jail, and when the woman couldn’t identify her assailant, the mob stormed the black neighborhoods in North and Central Beaumont. The 1943 Beaumont race riot left three dead.

Jones lived on the south side of town and was unaware of the riots until the next morning when he was going to catch a bus. Instead he was told, “‘Boy you ain’t gonna catch no bus, you gonna stay home — there’s a war going on!’”

Less than two months later, things had returned to normal and the area — known as “The Arsenal of Democracy” — returned to production for the ongoing war. Jones moved to California, finally returning at 70 to look after his aging parents. He says not much has changed, unfortunately.

“[White people] change their stripes, but they can’t change their mind,” he said. “White folks today are saying they love Blacks,” but he called the affection insincere — “an act.”

Jones said he is cautiously optimistic about President Joe Biden abundance of Black appointees to prominent jobs in the Federal government.

“He’s got a long way to go,” Jones says.

—Ramón Rodriguez