Research on Boozing Bugs Aims to Find Breakthroughs on Alcoholism Treatment

By Cate Malek

Reporting Texas

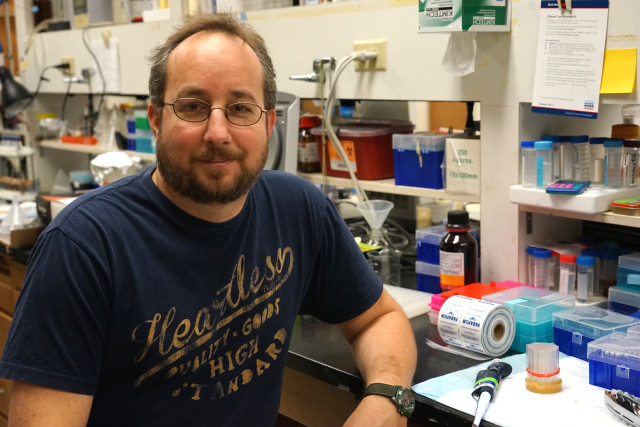

Dr. Alfredo Ghezzi, a University of Texas postdoctoral fellow, poses at his lab bench where he studies the effects of alcoholism by exposing fruit flies to ethanol. Jack Vrtis/Reporting Texas

Few people would imagine they had anything in common with a fruit fly.

But researchers have found that studying these tiny insects can reveal surprising insights into human beings, including memory, learning and alcohol addiction.

It turns out that, like people, many fruit flies are drawn to alcohol. And, like people, they can get very drunk.

“It’s pretty funny actually,” said Alfredo Ghezzi, a neuroscientist who has become an expert in getting fruit flies to consume alcohol. “They fly erratically, and then they start stumbling, and eventually they pass out.”

The tests may be entertaining to watch, but Ghezzi and other researchers at the University of Texas at Austin are using fruit fly research for a serious purpose: to understand how exposure to alcohol reprograms the brain’s neurons. That knowledge could help explain why alcohol addiction is so difficult to treat, and might even predict who is susceptible.

More than 16 million people in the U.S. have been diagnosed with alcohol use disorder, and heavy drinking causes 88,000 deaths a year, according to the National Institutes of Health.

“They call alcohol a dirty drug because it affects many targets in the brain,” Ghezzi said, compared to a drug such as nicotine, which have more specific targets.

Research shows that drinking is a brain disease in people with alcohol dependence, meaning it changes how their brains work at a cellular level. Alcohol dependence has a high genetic component. So Ghezzi and his colleagues are investigating which genes are involved in alcohol addiction.

Originally from Peru, Ghezzi, 39, has been working at Nigel Atkinson’s neuroscience lab since 2004. The lab, at the end of a long hallway in the Patterson Laboratories Building, is decorated with large-scale pictures of flies — including a Spanish poster from the 1958 cult horror film “La Mosca,” (“The Fly”) showing a giant fanged fly attacking a screaming woman. The shelves are lined with test tubes filled with alcohol-laden molasses (they use different types of alcohol). Groups of tiny, brown fruit flies swarm around the molasses.

One of the main questions driving the lab’s work is learning how the nervous system adapts to change. Researchers have learned that when the nervous system is thrown off-kilter by stress, toxins or even the changing seasons, it has mechanisms that help restore it to its normal state.

The device used by Dr. Alfedo Ghezzi to send ethanol vapors into the fly container, effectively making them drunk.

It turns out that these adaptive mechanisms also may be linked to addiction.

Ghezzi has been studying the genes involved in tolerance, one of the first adaptations the nervous system makes to alcohol consumption. Basically, as fruit flies drink more, they develop the ability to consume even larger amounts of alcohol without becoming incapacitated.

But that higher tolerance brings more intense withdrawal symptoms when the flies stop drinking. At that point, Ghezzi has found that their nervous systems are over-stimulated: they get jittery. Withdrawal might lead the flies to consume more alcohol to calm down, which could lead to addiction.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, a federally funded agency, provides most of the lab’s funding. The lab is part of an informal network of fruit fly researchers around the world all working to understand how these tiny insect respond to alcohol.

Some recent discoveries from other labs include that drunk fruit flies will lower their standards when choosing a mate. And when fruit flies are rejected by the opposite sex, they will eat less and consume more alcohol. Their larvae can also become functionally dependent on alcohol. Atkinson has found that larvae that have been exposed to alcohol on a regular basis can learn at a normal level only when they have ethanol – the type of alcohol used in beverages — in their systems.

The growing cache of knowledge about fruit flies makes them a useful study subject. Fruit flies are also easier and cheaper research subjects than mammals. Their short lifespans mean researchers can get results faster, because the fruit flies may produce hundreds of offspring in just a few weeks.

“If you want to do genetics, big numbers are always helpful.” Ghezzi said.

Although the Atkinson lab has been using fruit flies to study alcohol for almost 15 years, researchers have been able to increase the speed of their research almost exponentially in recent years because of improved technology. Ghezzi said that where it once took him several years to map one gene, he is now able to track the fly’s entire genome in less than a year.

As research progresses, the discoveries from the lab could have significant implications.

Carlton Erikson, a research scientist at UT’s College of Pharmacy who has been studying the effects of alcohol on the brain for over 45 years, said Ghezzi’s research could help identify the genes connected to alcohol addition, which could help diagnose and treat the disease.

“We don’t know exactly what’s gone wrong [in the brain] to cause someone to lose control of their drinking, but it must be genetically controlled in a lot of people,” he said. “If one gene goes wrong, or a couple of genes next to each other go wrong…you’re going to get interrupted signals, and then the person no longer has a choice over whether they use alcohol or not.”

If scientists can identify the genes behind alcohol dependence, the disease could be diagnosed before someone ever took a sip. Farther in the future, researchers might be able to develop a genetic treatment for alcohol disorders.

“It’s a possibility that if you could find how the gene goes bad…then you could somehow stop that gene and prevent the disease,” Erikson said.