Project Connect and Austin’s Past Light Rail Fails

By Harrison Young

Reporting Texas

A Herzog service worker steps off the Capital MetroRail to check Leander MetroRail Station for riders on Oct. 13, 2020. Capital MetroRail, a commuter rail system intended to transport people from the suburbs to downtown, started in 2010. Austin doesn’t have a true light rail system for intracity transportation. Kennedi White/Reporting Texas

The fate of the Oval Office is not the only key issue on Austinites’ ballot this November.

Project Connect, Austin’s proposal for a light rail system and widely expanded bus service, is on the ticket as Proposition A.

The alignment serves a greater portion of the city than past years’ plans but costs significantly more. However, the proposal also includes more features such as housing funds and additional bus routes.

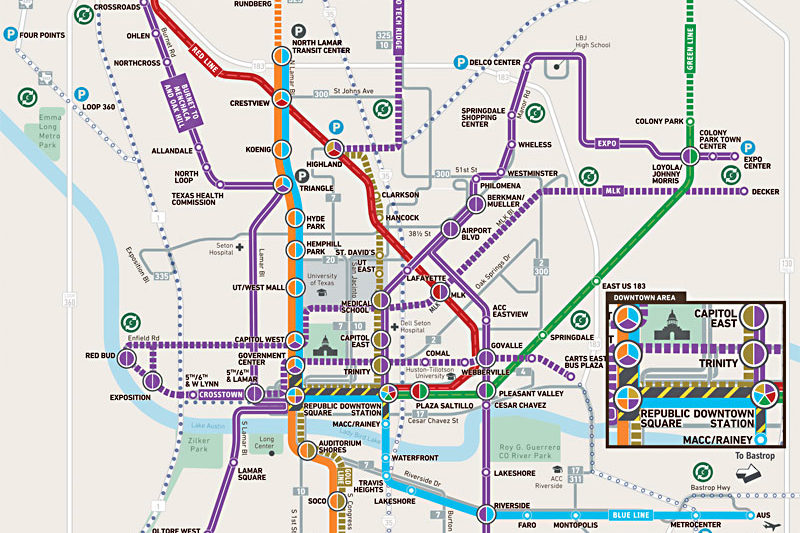

According to Capital Metro’s alignment map, the Orange light rail runs from North Lamar Transit Center south to Stassney Lane along the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. The Blue light rail parallels the Orange to downtown, then turns east toward Austin-Bergstrom International Airport. The MetroRail Green line begins in Colony Park and travels southwest to end downtown. The proposal also lays out an underground tunnel to connect the Republic Square station with the Downtown station.

The project is projected to cost $10 billion. The $7.1 billion initial investment will rely on an 8.75-cent property tax increase. The median price of a home in Austin is $435,000, according to the Austin Board of Realtors. The combined city, county, school district, community college and hospital district tax rate on that home this year is $2.23 per $100 of taxable value, for a total of $9,700.50. An 8.75 cent increase would raise taxes on the home to $10,063.73. Capital Metro seeks federal funding for the remainder of the budget, $3 billion. Project Connect’s overall buildout time, including environmental review and construction, is projected to take eight years.

The proposal’s hefty price tag has been met with protest. Peck Young, a spokesman for Voices of Austin, a voter education organization that opposes Austin city government policies on issues ranging from transportation and land use to public safety and spending priorities, believes “the only benefits are to the bureaucrats, engineers, architects and heavy construction companies that will make money off of building this thing.”

Transportation experts say Project Connect would not only alleviate traffic but also improve Austinites’ quality of life.

“Well-designed infrastructure along the path of the rail can significantly increase the quality of public space in the city,” said Dean Almy, a professor of urban design at the University of Texas-Austin.

Earlier this year, City Council massaged the bond proposal to include $300 million for anti-displacement measures to keep families in their homes as businesses develop along rail lines.

“Instead of displacing marginalized people, we keep them where they are while also building new affordable housing,” Council Member Natasha Harper-Madison said in a tweet from July.

Others criticize the provisions.

“The housing slush fund is a really bad idea that makes it more expensive to deliver transit while simply providing protection to incumbents at the discretion of City Council,” local urbanist Mike Dahmus said in an email.

This is not the first referendum of its kind in Austin. There were votes to expand transit in 2000 and 2014, but both fell short at the polls. To give voters perspective on the issue, Reporting Texas looked at Austin’s past rail fails.

2000

Planners hoped this plan would alleviate Austin’s traffic, a problem even then. While the proposal was minimal compared to the current one, it ran through crowded areas and provided service to much of the Austin metro population.

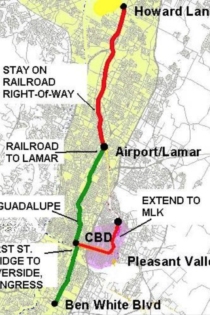

It was split across two lines, Red and Green. The Green ran from Ben White Boulevard to the Airport Boulevard-Lamar Boulevard intersection. The Red would pick up there and continue to Howard Lane via the Austin and Northwestern Railroad, owned by Capital Metro. A third line originated downtown and went directly to Austin-Bergstrom airport.

The city “missed the opportunity to get [the route] right before it went to ballot,” said Jeff Wood, an San Francisco-based planning consultant who studied Austin’s 2000 transit plan at UT-Austin.

The Federal Transit Authority budgeted the plan at $1.8 billion and pledged to pay for 50%. The other half was to come from bonds backed by a one-cent increase in the Capital Metro sales tax levy.

2014

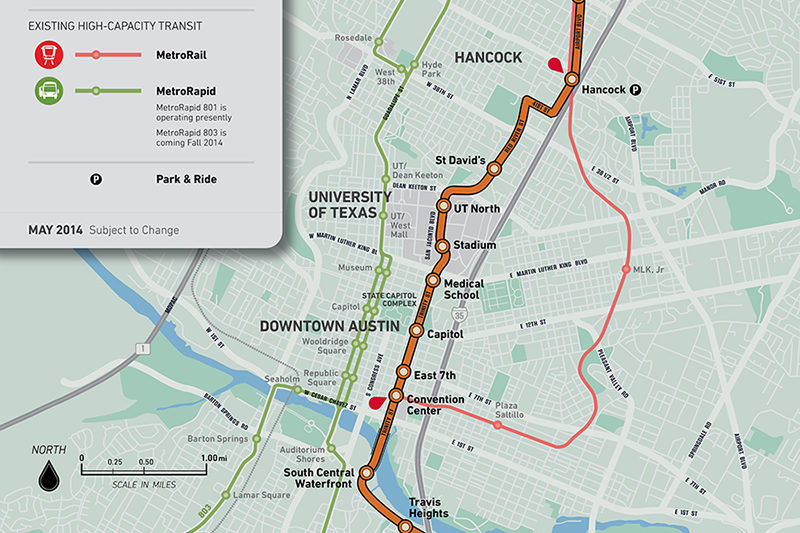

In 2014, the proposed routes for light rail were expanded since Austin’s population had grown. The route served less territory and did not include Austin’s most heavily populated areas, namely the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. Only one rail line and one bus line were in the proposal.

The train was planned to head from the Austin Community College Highland campus to south central shore of Lady Bird Lake, and then turn east toward the airport. The bus line came down Burnet and Lamar to meet at Guadalupe, traveled through downtown, and split on Cesar Chavez to go down South Congress and Lamar.

Transportation consultant Lyndon Henry wrote in a blog post that planners “appear to have virtually abandoned the core neighborhoods.”

“The alignment was such that it was focused on economic development,” Wood said. “The biggest effect on ridership is employment density.”

Planners were hoping that alignment would lead to more development along rail lines.

The project budget totaled $1.38 billion, with half of the project’s funds coming from the federal government and the other half from taxpayer-approved bonds.

Even train supporters welcomed the results of the election. Austin rail advocacy group Our Rail said it supported a train system with the right plan, but it opposed 2014’s route. The group opposed “mass transit investment that threatens the development of urban rail in the dense Guadalupe-North Lamar corridor.”

The Votes

Austin came closest to a light rail system in 2000, when the proposition was on the ballot along with George W. Bush’s first presidential bid. Austinites showed up en masse to support their then-governor.

The plan was expected to pass, and the Federal Transit Authority even placed Project Connect in front of other cities’ similar projects. The plan ultimately failed by less than 2,000 votes with over 300,000 votes cast.

Within Austin city limits, voters approved the measure, but since the territory polled included all of Capital Metro’s service area, voters outside of Austin tipped the decision.

The 2014 route was designed with 2000’s failure in mind, but served much less of the city and did not go down the extremely dense Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. To appeal to more residents, the package came with $400 million in road improvements.

The plan was voted down by a much wider margin – 57% voted against the proposition, compared to less than 51% in 2000. Pollsters at the time theorized the key factor was opposition to higher taxes, while others blamed the route that depended on future density instead of current population.

This year, experts are predicting increased local turnout in Austin because of the presidential election. Caleb Pritchard, a spokesman for Transit Now, remains cautiously optimistic. The pandemic “created challenges and uncertainties,” Pritchard said, adding that polling is promising. He expects a “huge turnout of younger, more progressive voters.

“It’s a matter of going all the way down their ballot,” he said.