Local Enthusiasm Key to Texas’ Nuclear-Waste Future

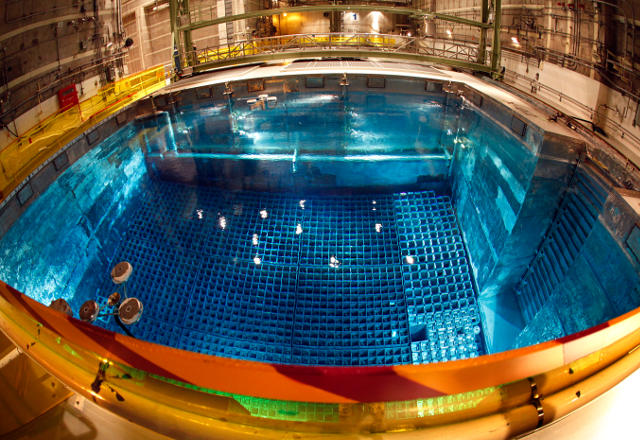

Spent fuel rods are submersed below 24 feet of water in the fuel building of the Comanche Peak nuclear power plant near Glen Rose, 80 miles southwest of Dallas. Photo by Tom Fox/The Dallas Morning News.

By Joseph Baucum

For Reporting Texas and the Austin American-Statesman

Texas House Speaker Joe Straus recently raised eyebrows among environmentalists and individuals connected to the nuclear waste industry. Unexpectedly opening the possibility of making Texas home to America’s supply of high-level radioactive waste will do that.

The United States lacks a permanent disposal site for 68,000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel after the Obama administration decided in 2010 to halt funding for the multimillion-dollar Yucca Mountain geologic repository in Nevada. Straus has charged state legislators to determine whether Texas can be the answer and “make specific recommendations on the state and federal actions necessary to permit a high-level radioactive waste disposal or interim storage facility in Texas.”

Gov. Rick Perry has endorsed the idea as well. “I believe it is time to act,” he said in a March 28 letter to Straus and Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst.

In an effort to avoid a replay of the decades-long controversy over Yucca Mountain, where the federal government imposed the site on unwilling local interests, the onus is ostensibly on local communities to step forward to host the nation’s most hazardous nuclear waste. The consensus-based approach is designed to be more democratic, but with millions of dollars potentially at stake for the state and officials tied to the waste industry, critics say determining Texas’ future in high-level waste could be politics as usual.

A new bottom-up approach was one of several recommendations from a 2012 Blue Commission Report to the Department of Energy. Former U.S. Rep. Lee Hamilton, D-Indiana, was co-chair.

“We think that looking at siting decisions not only in our country, but across the world, it’s a very complex set of negotiations that have to take place among a lot of actors at the local, state and federal level,” Hamilton said in an interview with Reporting Texas.

In the consent-based approach, state and local governments would encourage communities to volunteer as host sites, instead of the top-down model employed at Yucca Mountain.

Hamilton said any area serving as the nation’s disposal site would benefit from jobs generated during construction and subsequent operations. A substantial amount of money for the project would come from a $30 billion nuclear waste fund, which is fed by fees the federal government has collected from nuclear power plants since 1983. The plants now store spent fuel on site.

Texas environmental groups including the Sierra Club, Public Citizen and the SEED Coalition oppose the idea of Texas taking on high-level nuclear waste. Waste Control Specialists, which operates a low-level waste facility in Andrews County, west of Midland on the New Mexico border, would like to be involved if lawmakers vote to move forward. WCS, based in Dallas, is the only company in Texas handling low-level waste disposal. It’s also the only destination for some of the most radioactive low-level waste in America.

The House Committee on Environmental Regulation will investigate Straus’ charge. Six of the nine members are Republicans. Through a spokesperson, chair Patricia Harless, R-Spring, declined to comment on whether the committee would use the consent-based methodology recommended by the commission report. The report was the primary influence on Straus’ decision to add the issue to his charge to the committee, a spokesperson for the speaker said.

Between legislative sessions, the speaker customarily instructs the various House committees to explore and report on a set of issues. The interim charges, as they are called, signal his priorities for the next Legislature.

Billionaire Harold Simmons, who died in December, owned WCS, and a Simmons family trust now owns a majority of the stock. Simmons was one of the nation’s most generous Republican political contributors, donating more than $25 million to Republican super PACs in the 2012 presidential election, according to Forbes.

Simmons donated $2,500 to Perry during his failed bid in the last presidential election. Contran Corp., another Simmons business, donated $1 million – more than any other contributor — to Make Us Great Again, a super PAC that supported Perry’s campaign, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Straus has received $100,000 since 2011 from WCS-Texas Solution, a political action committee run by WCS. Seven members of the environmental regulation committee have received $42,000 from WCS-Texas Solution in that time period. Their total contributions in the same period from all sources were nearly $3.5 million.

| WCS-Texas Solution contribution recipient | Amount | Date |

| Patricia F. Harless | $1,000 | 10/06/11 |

| Patricia F. Harless | $1,000 | 03/12/12 |

| Committee to elect Jason Isaac | $2,500 | 10/31/12 |

| Committee to elect Jason Isaac | $1,500 | 08/28/13 |

| Kyle J. Kacal | $1,500 | 07/23/13 |

| Tryon D. Lewis | $6,000 | 06/27/13 |

| Friends of Ed Thompson | $2,500 | 02/17/12 |

| Friends of Ed Thompson | $3,000 | 03/06/12 |

| Friends of Ed Thompson | $1,500 | 07/23/13 |

| Christopher G. Turner | $1,000 | 05/02/12 |

| Christopher G. Turner | $1,500 | 07/25/13 |

| Texans for Jason Villalba | $2,500 | 03/30/12 |

| Texans for Jason Villalba | $5,000 | 06/14/12 |

| Texans for Jason Villalba | $1,500 | 10/31/12 |

| Texans for Jason Villalba | $10,000 | 10/10/13 |

| Texans for Joe Straus | $25,000 | 08/04/11 |

| Texans for Joe Straus | $50,000 | 11/01/12 |

| Texans for Joe Straus | $25,000 | 10/21/13 |

| Data from the Texas Ethics Commission |

WCS-Texas Solution has been one of the main PAC sources of campaign donations to lawmakers, according to Cyrus Reed, conservation director for the Texas chapter of the Sierra Club, but he said he doesn’t think the committee members have been bought off. Reed says how many lobbyists a group fields on a particular issue is just as important as contributions. Reed is the only registered lobbyist for the Sierra Club. WCS has five lobbyists.

“The lobbyist is important, because if you’ve got a number of people you’re paying that are there full-time, it just means you’re going to get better access to members and be able to make your point easier,” said Reed.

WCS has generated $16 million in revenue for the state since beginning disposal of low-level waste in July 2012, according to the company’s website. Texas receives 25 percent of the facility’s gross disposal fees. WCS does not disclose financial reports, but spokesman Chuck McDonald estimates the company’s revenues at $40 million annually.

McDonald says the company did not speak with Straus’ office about the committee charge but would like to be considered, if Andrews County and the state are amenable. He says community leaders would need to show interest before WCS pursued anything. State revenue from the WCS operation is likely to grow if the site adds high-level nuclear waste.

“We have been in dialogue with the community, and we’ll continue to be,” said McDonald. “If our host community says, ‘This is something we’re interested in and this is something we’re comfortable with,’ WCS would like to be part of the solution.”

Austin-based AFCI Texas is also interested in whether the committee identifies any communities that would be receptive to a disposal site. The company has been in talks with several West Texas counties about building an interim storage facility for spent fuel now held at the Comanche Peak nuclear power plant in Somervell County and the South Texas Project in Matagorda County, according to AFCI co-owners Bill Jones and Monty Humble.

AFCI would need federal approval to store the used nuclear fuel as well as a license for transporting it to the site, but the company is interested in the House committee’s findings to gauge Texans’ level of comfort with the idea.

“I don’t want to sound so arrogant as to suggest that if the state were fundamentally opposed to it that we’d still be enthusiastic about pursuing it,” said Humble. “I don’t think we would.”

The committee will hold public hearings and take testimony from anyone interested in the issue, according to a Harless spokesperson. No hearings have been scheduled.

In the past, the committee has sided with industry, according to Reed of the Sierra Club. He points to its failure to pass measures including stricter regulation of coal plant emissions and improving awareness on mercury emissions. Harless’ office declined to respond to his comments.

“Generally, the committee is not going to pass something that industry is very opposed to,” said Reed. “They’ll look more for solutions that industry can live with.”

Reed said he doesn’t think current committee members are closed to environmentalists’ concerns. He cites compromises the committee struck during the 83rd Legislature when it allowed WCS to accept low-level waste from out of state but gave permission to handle less than it had wanted.

The main concern, according to Reed, is what legislation could come out of Straus’s charge.

“Once you put out an idea, it can gather its own steam,” Reed said. “There’s a concern from our point of view that you start putting out there that we’re studying it, and suddenly everybody says, ‘Texas is going to step up to the plate and provide these services. We better write legislation so we can make that happen.’ ”

McDonald, the WCS spokesman, said he thinks the process will be fair. He noted that the legislation authorizing the company to accept waste from other states passed by a 131 to 10 vote, with 70 percent of Democrats voting yes.

“There have always been changes and compromises made to the legislation,” said McDonald. “I think it’s fair to say that what has emerged has been, legitimately, consensus legislation. That’s why it’s had strong bipartisan support.”

If the committee recommends moving forward, the issue will go before the 84th Legislature in January. Should the state decide to support a high-level waste repository, it would require federal approval.