La Belle Makes Final Voyage from Mud to Museum

By Wes Martin

Reporting Texas

James Bruseth, guest curator at the Bullock Texas State History Museum, with tools recovered from the La Belle, which sank in the Gulf of Mexico in the 17th century. Photo by Lukas Keapproth/Reporting Texas

The skeletal wreckage of a 17th-century French warship lay buried deep in the mud of Matagorda Bay for more than 300 years.

But on Saturday, La Belle will make its final port of call – the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin.

The 60-foot keel of La Belle and more than 1.6 million artifacts of a doomed French settlement effort are all that remain of a colonial fleet meant to establish control over the Mississippi and permanently incorporate this part of the New World into Louis XIV’s empire. The expedition, which met its grisly end in Texas, was led by French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle.

The opening of the exhibit, titled “La Belle: The Ship That Changed History” marks the culmination of a hunt that has taken the better part of a lifetime for Jim Bruseth, guest curator at the Bullock and director of recovery efforts for the Texas Historical Commission. Bruseth and his staff discovered the wreck and painstakingly restored artifacts that were preserved by the silty seafloor of the Gulf of Mexico.

“Historians for a century and a half have been writing about La Salle coming to Texas and La Belle and where it was,” Bruseth said over the din of construction on the exhibit. It’s “absolutely electrifying to see the ship.”

The $10 million exhibition will eventually include a reconstructed La Bell displayed under a glass walkway at the museum. A French delegation will attend the opening Saturday to begin the repatriation of some artifacts to a French marine museum.

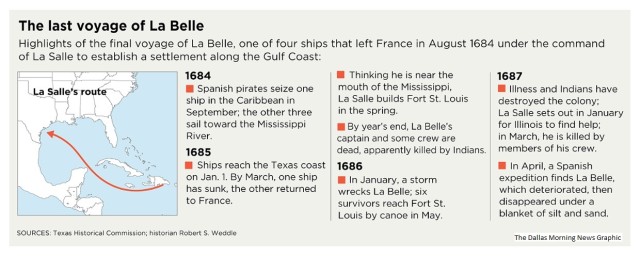

Pirate attacks, hostile natives, inaccurate charts and inhospitable weather plagued La Salle’s expedition of four ships and 300 colonists when they arrived in the Gulf of Mexico in 1685, according to documents Bruseth and his staff studied. The French explorer landed 500 miles west of the Mississippi River while searching for its mouth under a royal commission to establish a colony to maintain France’s holdings.

“He started with four ships, lost one to pirates in the Caribbean, lost another in Pas Bayou in Matagorda Bay,” Bruseth said. “The third ship had orders to offload supplies and colonists and sail back to France, which it did. La Belle was his last lifeline. So when he lost that in 1686, he realized his colony was about to be completely doomed.”

The 27 remaining members of the expedition were surrounded by hostile American Indians and risked execution if captured in Spanish territory to the south. So they began a long walk to Canada.

Bruseth said the Spanish quickly realized that French explorers had entered their part of the New World and feared the machinations of Louis XIV.

“They realized that if they were going to stop France from coming back, they needed to occupy Texas,” Bruseth said. “And so La Salle’s coming to Texas — the failure of it because of the sinking of La Belle — opened the door and allowed Spain to come up. And that’s what’s left us with our wonderful Hispanic heritage that we have today.”

Disenchanted with their leader, the remaining members of his expedition murdered La Salle somewhere in East Texas. One of the six who made it back to France was the ship’s pilot, who kept detailed records of the expedition’s catastrophic voyage.

Those records, along with Spanish maps that attempted to track the French colonization efforts, led Bruseth and his team from the Texas Historical Commission to the final resting place of La Belle.

“Based on that Spanish map, we’d been looking for La Belle since the 1970s,” Bruseth said. “And then in 1995 we resumed the search and luck was with us.”

Using a massive shipborne metal detector, the team found the shipwreck. A year later, they installed a cofferdam — a large steel wall around the wreck site — to recover it.

“We pumped the water out and excavated it like it was a land archaeological site,” Bruseth said.

Before reconstruction work could begin, though, a diplomatic dispute erupted when France claimed ownership of the ship.

Ultimately, a treaty signed at the White House in 2003 settled the dispute. The Texas Historical Commission got custody of the wreck, but France still retained title to it.

The recovery team still faced the formidable task of removing, preserving and rebuilding the wreckage. Peter Fix, an archaeological conservation specialist at Texas A&M University who heads reconstruction efforts, called the work “a combination of shipbuilding and reverse-engineering.”

Fix and his crew have been at work on the La Belle since the excavation was completed.

“At this point, we’ve had to rebuild the boat about four or five times,” he said.

“We put these timbers in a freeze dryer at Texas A&M that’s 40 feet long,” Fix said. “Over a period of four and a half months, we froze it and slowly pulled the water out of the wood.”

Fix said the ship was in a sorry state.

“Shipworms ate probably about 60 percent of this ship and burrowed throughout the remaining beams,” Fix said. “If you took a cross section of the keel, it looks like Swiss cheese.”

Fix and a team of experts will be rebuilding the 600 ribs and other remains of La Belle while fielding questions from visitors to the exhibit during a live reconstruction expected to last several weeks.

The exhibit includes a 3-D immersive movie called “Shipwrecked.” The state contributed $2.2 million, and the rest was funded by private donations, Bullock museum spokeswoman Elizabeth Page said.