Gender Gap Among STEM Faculty at UT Proves Difficult to Eradicate

By Eniola Longe

Reporting Texas

Karen Willcox, an aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics professor at the University of Texas at Austin, left, listens as a gradate student talks about their project at an open house event in the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Building on March 7, 2022. Jessie Curneal/Reporting Texas

As a child, Karen Willcox dreamed of being an astronaut. Spurred by the love of spacecraft in “Star Wars,” Willcox studied engineering at the University of Auckland in New Zealand.

“The year I enrolled in the engineering school, 1990, was the very first year my school had 20% female enrollment,” Willcox said. She had one female professor during four years of undergraduate studies. “I think it makes a very big difference because we all feel more comfortable and more inspired when we see people we can identify with.”

The lack of female role models didn’t prevent Wilcox from graduating and getting advanced engineering degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Today Willcox is a professor of aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics at the University of Texas at Austin.

UT and other universities around the world have worked to address gender inequity in science, technology, engineering and math fields, but a lack of female role models in STEM and entrenched gender norms have made the disparity difficult to eradicate.

At UT-Austin, women make up 45% of the total faculty, but a much smaller percentage in STEM majors. The departments of aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics, electrical and computer engineering, geosciences, mechanical engineering and physics all have less than 20% female faculty.

Karen Willcox, an aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics professor at the University of Texas at Austin, poses for a portrait at the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Building on March 7, 2022. Jessie Curneal/Reporting Texas

Aware of the problem, many of the STEM departments have diversity efforts in progress. The university began a Women in STEM outreach program in November 2021. UT-Austin’s Cockrell School of Engineering started its Women in Engineering Program in 1991 and the College of Natural Sciences launched the Women in Natural Sciences program in 2001.

Other efforts include the University Faculty Gender Equity Council, started in 2014, which is tasked with advancing gender equity among all UT faculty.

“We’re graduating women at the same rate as men, no gender difference there,” said Tricia Berry, director of the Women in Engineering Program. “The difference is that we have fewer women who are heading into PhD programs than their representation in the undergrad space.”

“As you move from the undergrad level, to the master’s, PhD and female professors, the numbers go down,” Willcox said. “So the pipeline is still very leaky.”

Lizy John is a professor of electrical and computer engineering at UT-Austin who attended college in India. She did not have a female STEM professor until her junior year, she said. When faced with a problem in a STEM class, she hesitated to ask male professors for help and felt more comfortable interacting with female professors, she added.

“Although there is some small improvement, it is much less than what is needed,” John said. “More work should go into encouraging women to come and in helping the women who have already come.”

John is working to put female STEM graduate students into positions where they are role models. “Wherever more women could be included, I have paid attention and made it happen,” she said.

In the search for teaching assistants, John said she tries to hire female applicants, as long as they are qualified. “My female students have TA’d for predominantly male classes and handled it very well,” she said.

With over 20 years leading gender diversity efforts in STEM fields, Berry says the scarcity of role models in STEM graduate studies makes it daunting for recent graduates who often see women in corporate jobs in other industries.

Recruiting candidates into graduate programs where they are paid much less than a corporate job is difficult, Berry said, and she has seen many women who study STEM in college go straight into the workforce rather than pursue graduate study.

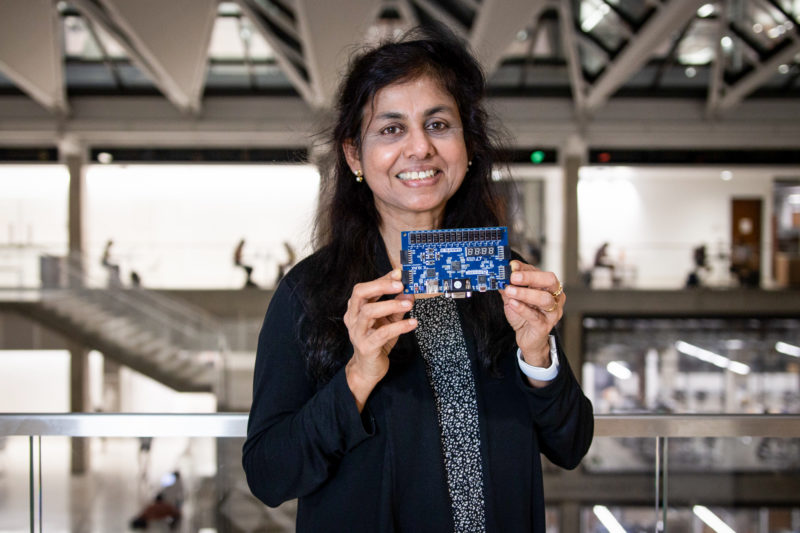

Lizy John, an electrical and computer engineering professor at the University of Texas at Austin, holds a field-programmable gate array development board in the Engineering Education and Research Center on Feb. 21, 2022. Jessie Curneal/Reporting Texas

Sachi Kulkarni, a public health major at UT-Austin, decided to work with Women in STEM, one of the initiatives under UT Austin’s division of diversity and community engagement, because she wanted to build a mentorship network of women.

“All of my bosses are really amazing women who have done a lot trying to advance equity in the sciences and engineering,” Kulkarni said. “It’s been really great getting to know these women, since we’re underrepresented in the sciences.”

As a program assistant, Kulkarni has met women in STEM and serves as a mentor to K-12 students through the initiative’s Girl Day at UT-Austin program, which is designed to increase awareness of and interest in STEM fields.

University of Oklahoma psychology professor Adrienne Carter-Sowell studies and writes about the lack of diversity in STEM fields. The dearth of female role models should be addressed as early as kindergarten, she told Reporting Texas.

“There’s a study in psychology of kindergarteners: When they draw a picture of a scientist, they draw a picture of Einstein, male, lab coat, crazy,” Carter-Sowell said. “This sends a message that this field is not represented by you, to the kids who don’t even know what scientists really do.”

Research shows that cultural norms about femininity also contribute to the problem. Girls are often encouraged to find careers that are family friendly, like nursing and teaching, because they provide them with flexibility, Carter-Sowell said

“They’re either encouraged to do courses that make them attractive partners,” Carter-Sowell said. “If they’re expected to have jobs, they’re expected to have jobs that are family friendly.”

“I have never heard anybody tell a 10-year-old boy who has all options on the table, but which one of these will allow you to be home by 5, to get the kids when they get off from school?” she said.

Norms can also be related to things like stereotype threat, says Agatha Beins, gender studies professor at Texas Woman’s University.

“This is when negative stereotypes — such as girls aren’t good at math — can affect academic performance,” Beins said. “When people are worried about reproducing stereotypes, they might not perform as successfully in academic tasks.”

Apart from the lack of role models, as women move up the educational ladder, the initial support received from family and friends begins to wane, Carter-Sowell said.

“If you’re the smartest one in your family, everybody’s really proud of your achievements,” Carter-Sowell said. “If you’re a female, people say, ‘Oh, you don’t need any more degrees; you need to get a family.’”

If gender disparity in STEM faculty isn’t addressed, scientific progress will suffer, she added.

“We are not reaching potential because we’re not involving enough women in the process,” Carter-Sowell said. “Not having women involved in these developmental processes is a disservice.”

Beins agrees.

“When people with different backgrounds, life experiences, skills, and perspectives work together to address a problem,” Beins said. “They come up with more creative solutions and develop solutions that are sensitive to the needs and experiences of different social and cultural groups.”